Ships or collieries?

The sale of the Graig early in 1922 left the company with no material investment, and it would appear that this was a period during which there was some disagreement at board level about the company’s future course. With the cost of tonnage having fallen considerably and shipyards across the UK crying out for work, Idwal Williams proposed that this was the ideal time to invest in a new ship and in November 1922 it was agreed that an order be placed by Graig Shipping with Robert Duncan and Co. of Port Glasgow for a 3,683 gross ton steamship of long bridge deck design. Delivered in April 1924, she was designed particularly with the River Plate grain trade in mind, being capable of loading 7,050 deadweight tons on a maximum draft of twenty-three feet, which would enable her to cross the notorious Martin Garcia Bar fully laden. However, the expertise of two of the other directors, Frederick Jacob and C.E.M. James lay in collieries, and their influence led in October 1923 to the purchase of a controlling interest in the New Brook Colliery Co. Ltd, which had a nominal capital of £15,000. The company owned an anthracite mine (worked by a slant), formerly known as the Tyle Penlan Colliery, near Cwmllynfell, some fourteen miles north-east of Swansea, and Graig directors C.E.M. James, Idwal Williams and George Williams joined existing directors D.T. Edwards and W.J. Davies on the board of the New Brook company; a local mining engineer, B.E. Rees, joined the board on 1 April 1925.

Though not an obvious acquisition for what was established as a shipping company, the purchase of an interest in an anthracite colliery showed considerable commercial sense at that time, because the anthracite mined in the western end of the south Wales coalfield supplied a very different market from that of the steam coal of the central part of the coalfield. Whereas steam coal went chiefly to power ships, railway locomotives and factories, anthracite was more typically burnt as a domestic fuel, and in greenhouses, maltings and limeworks, where its intense heat and smokeless qualities made it an ideal fuel. This different market also meant that anthracite was not subject to the same drastic decline in prices that hit the steam coal trade in the inter-war years, as the European market was flooded by German reparations coal and competition from oil began to bite. New Brook was profitably producing some fifty tons per week when Graig took its first interest. Considerable investments followed at the colliery; new coal-handling machinery was installed, new loading sidings laid off the Midland/L.M.S. branch railway to Brynaman, a fleet of twenty new coal wagons was ordered from the Gloucester Railway Carriage and Wagon Co. Ltd. and the workforce increased from thirty to over one hundred. Output rose to nearly 200 tons per week, but disappointingly, despite these investments, the colliery’s overall profitability was not substantially increased, which started to lead to doubts on the Graig board as to the long-term viability of the investment.

Back on the shipping side of the business, the new ship, also named Graig, had been delivered in April 1924 and was trading reasonably profitably in the depressed market of the time. With capital still available, prices remaining low and yards still desperate for business, it was decided to order an identical sister vessel to the Graig (2) from the same builders and the 3,697 gross ton Graigwen was ordered for delivery in February 1926. By the time that she joined her sister vessel at sea, however, Graig’s involvement in the New Brook Colliery had been terminated. Strikes by the miners in the anthracite coalfield in July and August 1925 had hit production, and B.E. Rees, who also a director of another local (and neighbouring) colliery company, the Pwllbach, Tirbach and Brynamman Anthracite Collieries Ltd. would seem to have brokered the negotiations between this company and Graig for the former’s acquisition of the New Brook Colliery on New Year’s Day, 1926. Reflecting the improvements made at the colliery, the sale price was £30,000, with £5,000 being paid in cash and the remainder in Pwllbach, Tirbach and Brynamman debenture stock. The colliery was eventually abandoned in November 1935, having lain idle for several years.

One of twenty new rail wagons ordered for New Brook Colliery. [Gloucestershire Archives]

Tramping through the Depression

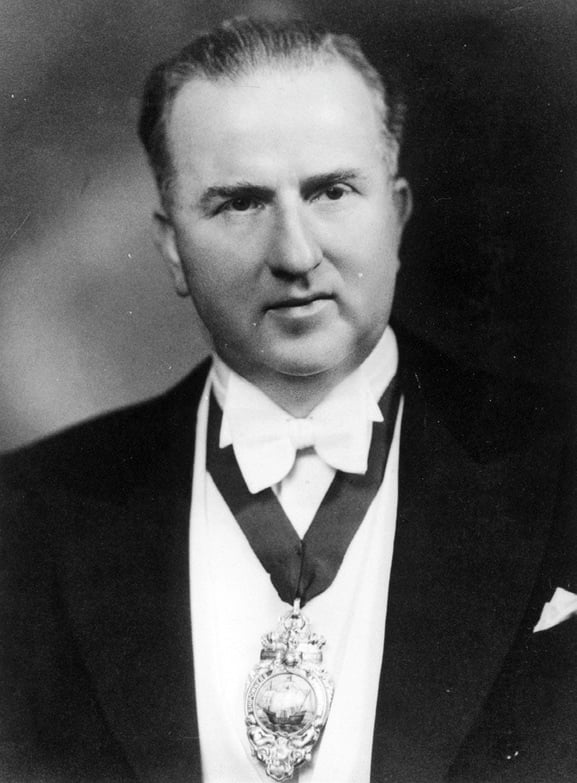

Following the sale of the New Brook Colliery and subsequent disagreements at board level, C.E.M. James resigned from the board on 28 October 1927 and he was followed by Frederick Jacob, who resigned on 31 March 1928. This left Graig Shipping in the hands of a much-reduced board of the management firm, Idwal Williams and Co., comprising George Williams as chairman and Idwal Williams as managing director and company secretary. They took charge of the venture at a time when there was some hope that the shipping market would improve, but these hopes were cruelly dashed by the Wall Street crash of October 1929 which led to four years of abject depression for the tramp shipping industry world-wide. By June 1933, freight rates were at an all-time low. The best homeward rate for grain from the River Plate that summer was 8s 6d per ton, a stark contrast with the 60s per ton that had prevailed in the summer of 1919.

In order to improve the economic operation of the company’s two ships, it was decided to invest in the ‘re-heat’ system introduced by the North Eastern Marine Engineering Co. Ltd. at the time, which re-heated the steam used in a ship’s triple expansion engines and which the company claimed could lead to a saving in coal consumption in a typical tramp of the time of up to five tons per day. The cost of installing the system in the Graig (2) and the Graigwen was estimated at about £6,000 for each ship and Idwal Williams approached the company’s bankers, hoping to obtain loans to cover the cost. Unlike the years immediately after the war when the banks were willing to lend money to shipping companies almost without question, the prevailing economic circumstances had hardened the bankers’ hearts and the request for funding was turned down, with the bank even adding a suggestion that the firm sell one or both of its vessels!

This Idwal Williams was certainly unwilling to do, so he travelled to Sunderland for direct discussions with the directors of the North Eastern Marine Engineering Co. Ltd. His proposal to the company’s directors was that if they would install their system in both ships, he would immediately pay one quarter down, with the balance being reimbursed in quarterly payments over the following year. And

as security to cover the expenditure, he was willing to deposit the above-mentioned Pwllbach, Tirbach and Brynamman Colliery debentures, worth £25,000, with North Eastern Marine Engineering. Idwal Williams’s forthright honesty clearly impressed the directors of North Eastern Marine Engineering, and after conducting some enquiries as to the status of the company and Idwal Williams’s personal reputation, an agreement was reached and the installation of the machinery went ahead, resulting in considerable cost savings in the running of both ships during those difficult years. Such was the impression that Idwal Williams had made that it also resulted in Idwal Williams and Co. being appointed agents for the North Eastern Marine Engineering Co. Ltd. in south Wales and the south of England! The continuing difficulties arising from the depressed shipping market were reflected, however, in a decision taken

on 22 February 1937 to reduce the share capital of the Graig Shipping Co. Ltd. from £100,000 to £25,000; shares formerly valued at £1 were reduced in value to five shillings. This did have the advantage of enabling the company to pay a small dividend that year, having not paid one since 1921.

The voyage patterns of the Graig (2) and the Graigwen during the difficult 1920s and 1930s indicate that the outward coal trade to the River Plate, with return voyages of cereals (‘coal out, grain home’) remained important, but that Idwal Williams also used his skill and intimate knowledge of the tramp shipping trades to direct the two vessels elsewhere when opportunities arose. On 7 January 1925, for instance, the Graig passed Lloyd’s signal station at Land’s End bound ‘Plate for orders’ with a cargo of coal. This cargo was eventually discharged at Rosario, where she loaded grain for Odessa. Such a voyage would have been unimaginable prior to the First World War, when Odessa was Russia’s foremost grain-exporting port on the Black Sea, but this fixture reflected a continuing demand for imported cereal supplies in the infant USSR following the repeated harvest failures and resulting widespread famine of the years 1921-23. She arrived in Odessa on 9 March and having discharged, ballasted across the Black Sea to Poti where she loaded manganese ore for Garston on the Mersey. By 15 May she was back under the tips in Cardiff’s Queen Alexandra dock loading coal for the Argentinean market again.

It was (and indeed is) rare for a company owning just two ships to have both vessels in the same port at the same time, but this was the case repeatedly in the late summer and autumn of 1935 when both the Graig and the Graigwen kept close company. In late August that year, both were loading cereals at Rosario. And having loaded, both vessels were bound for the same port, Derry in Northern Ireland. The Graigwen was the first to sail on 9 September, followed shortly afterwards by the Graig; mid-October saw both vessels anchored on the River Foyle discharging their cargoes. November saw both vessels back in south Wales, both loading coal at Barry before heading for the Plate once more. Such were the difficulties that the tramp shipping industry continued to face at that time however, that calls were made to the government of the day to support the industry, which eventually responded in May 1934 with a White Paper entitled the ‘British Shipping (Assistance) Act’. Eventually enacted in 1935, the so-called ‘Scrap and Build’ Act comprised two main provisions.

Idwal Williams photographed in 1938 whilst he was Chairman of the Cardiff and Bristol Channel Incorporated Shipowners’ Association.

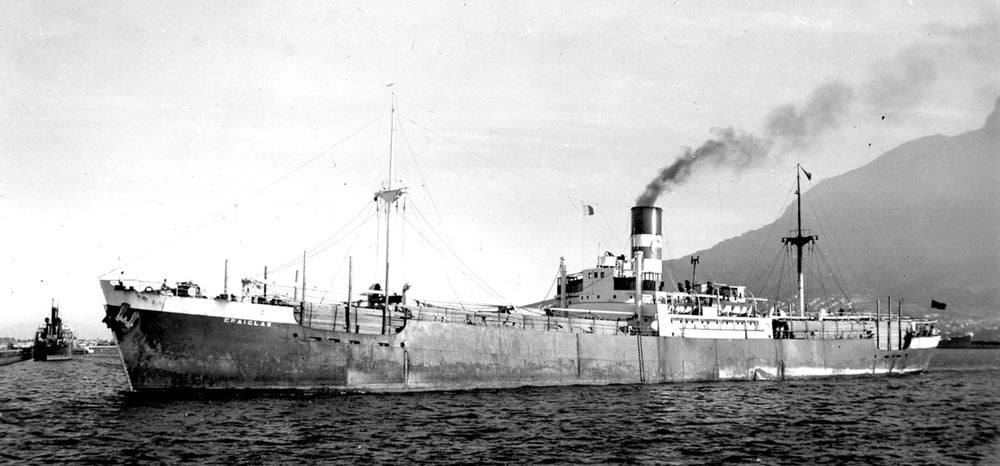

A £2m subsidy for tramp shipowners in 1935. The provision of loans to enable shipowners to buy obsolete tonnage for scrapping at a ratio of two obsolete gross tons to each gross ton of newbuilding, with most scrapping to be undertaken in the UK and all newbuildings to be ordered from British yards. The bill was criticised by the Opposition who derided it as ‘the shipowners’ dole’, but not all shipowners were in favour of the act either. In Cardiff’s shipowning circles, there was no more stern a critic than Idwal Williams. At a special meeting of the Cardiff and Bristol Channel Incorporated Shipowners’ Association convened on 15 May,1934, to discuss the White Paper, he noted that whilst the proposals would have the beneficial effect of removing out-dated tonnage from the market, he felt nevertheless that those owners who acquired new tonnage through the scheme would have an unfair and subsidised advantage over those owners already operating up-to-date tonnage, who chose not to participate. He continued to voice criticisms during his term as chairman of the Association in 1938. During the following year, a new British Shipping (Assistance) Bill was passed which made further provision for an annual subsidy of £2.75m each year to the UK cargo shipping industry until 1944 (international events eventually overtook this provision) and a £10m provision to make loans available to UK shipowners ordering ships from UK shipyards on or after 29 March 1939. Despite his prior opposition to subsidies, the terms of the 1939 loan arrangement clearly proved appealing to Idwal Williams, for that year the company placed an order with Joseph L. Thompson and Sons of Sunderland for a new steamship of 4,312 gross tons to be built with the aid of a loan; she was to be named Graiglas. Again designed specifically for the River Plate grain trade, she was slightly unusual in appearance; built to the same long bridge deck design as the Graig (2) and the Graigwen, she differed in having a raked bow, cruiser stern and a composite superstructure, with the hatch for the number 3 hold being located immediately forward of the bridge. An option for a second vessel was also considered but the UK’s declaration of war upon Germany on 3 September 1939 led to this option being dropped. For the next six years, everything that the company did would be governed by the war at sea.

Graig at war

The UK government acted more decisively at the outbreak of the second global conflict than it had in the first. All British ships were immediately brought under government control, as were their insurance arrangements. And unlike in the First World War, when the Admiralty had arrogantly doubted its value, the convoy system was also instituted from the outbreak of hostilities, though the lack of suitable convoy protection vessels proved a great weakness at the outset. Ironically, the first Graig loss of the war was not due to enemy action, but to the ever-present threat, whether in peace or war, of adverse weather. On 4 May 1940 the Graig (2) was on passage to join an eastward-bound convoy with a cargo of timber loaded at Halifax, Nova Scotia; at about 11pm that evening, in dense fog, she ran aground on Flint Ledge, Egg Island, some sixty kilometres east of Halifax, and subsequently broke in two. All thirty-four crew members got ashore safely, one suffering a broken leg. The two halves of the vessel were subsequently salvaged and taken to Halifax for scrapping.

Graiglas of 1940, off Cape Town. Ships in Focus

The new Graiglas was delivered later that month; unlike her two earlier sisters, she would survive the war. The Graigwen was lost on 9 October 1940 when she was torpedoed by U 103 about 250 miles west of the Hebrides, inward bound with a 6,160 ton cargo of maize from Montreal to Barry Roads for orders; seven out of her crew of thirty-four were lost, and the survivors rescued. Despite having been badly damaged, the Graigwen stubbornly remained afloat, and it took a second torpedo the following day from U 123 to send her to the bottom. Ordering new tonnage to replace the lost ships was impossible at that time as almost all slipways in UK yards had been turned over to build naval vessels, so Graig had to resort to the second-hand market as and when a suitable replacement vessel might become available. Such an opportunity arose in January 1941 when the company was able to purchase the 1925-built, 4,212 gross ton Newton Pine from the Tyneside Line Ltd (J. Ridley, Son and Tully) of Newcastle upon Tyne; wartime restrictions on changing vessels’ names meant that she was never given Graig- nomenclature. Indeed, her period of service with Graig was destined to be short-lived as on 16 October 1942 she lost contact with convoy ONS 136 in heavy weather, having sailed from Loch Ewe the previous day, bound from Hull to Halifax in ballast; German sources would later claim that she had been torpedoed by U 704. Her entire crew of forty and seven naval gunners was lost.

1 May 1941 saw the establishment of the Ministry of War Transport, which would oversee all merchant shipping for the remainder of the war. This was also the year in which a series of standard merchant vessels of various types and sizes, all given the Empire- nomenclature, began to be delivered from UK yards for allocation to British merchant shipowners; a meeting was held between the ministry and the Chamber of Shipping early in 1942 at which agreement was reached regarding the allocation of these new ships to companies in relation to the losses sustained by those companies, and the nature of those companies’ trades. The need for such an agreement had been amply demonstrated in May the previous year when the first of the newly-built Empire- ships to be allocated to Idwal Williams and Co. was Empire Brook, built to a basic East Coast collier design and at 2,852 gross tons, half the size of the tramps operated by Graig! She was soon transferred away from Graig to specialist East Coast collier operators France, Fenwick and Co. of London.

The following year saw two more appropriate vessels being allocated to Idwal Williams as managers. The 7,174 gross tons Ocean Vulcan was completed at a Californian shipyard in 1942, one of a series of ships built in the USA to a British design at that time before the Liberty ship programme got fully underway; she came under Graig management in May 1942. Then in October that year she was joined by the 7,136 gross tons Fort Chipewyan, completed at a Vancouver shipyard, also in 1942, one of a series of identical tramps, again built to a British design, but in Canadian shipyards throughout the duration of the war. Further additions to the managed fleet were made in December 1942 when the 6,965 gross ton Empire Foam, built by Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson of Newcastle, was allocated to Idwal Williams and in April 1944, when the 5,970 gross ton Empire Mariott, built by Pickersgill and Sons of Sunderland was similarly allocated.